Source – shift.newco.co

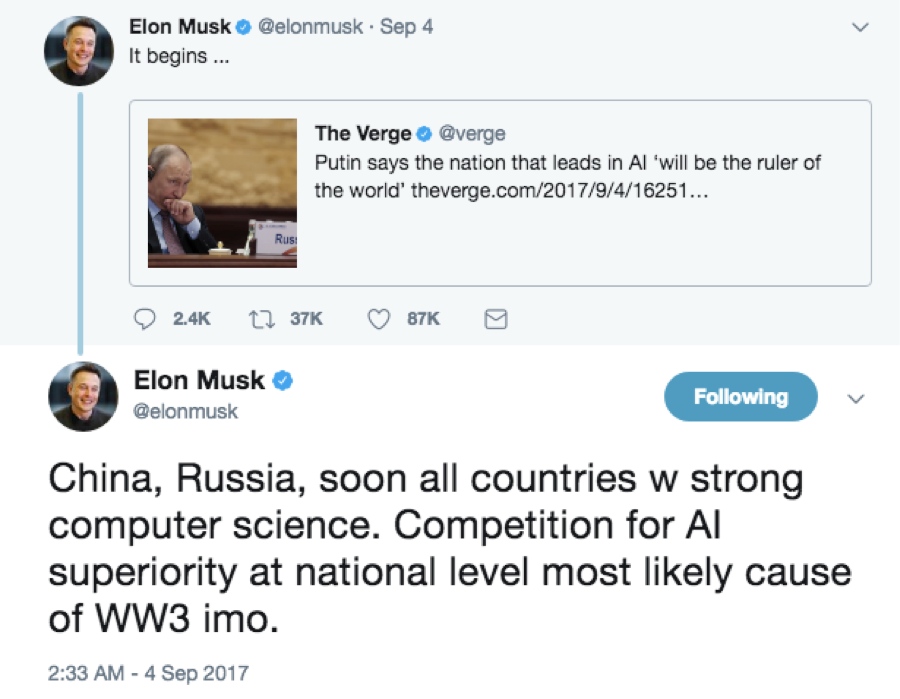

No stranger to controversy, a Tony Stark reincarnate — Elon Musk — came out with an ominous prediction recently. “Forget North Korea, AI will start World War III” read the CNN headline. Elon Musk is not alone in fearing unintended consequences of the race to develop algorithms that we may or may not be able to control. Once a new technology is introduced it can’t be uninvented — Sam Harris points out in his viral TED talk. He argues that it’ll be impossible to halt the pace of progress, even if humankind could collectively make such a decision.

The critics and cheerleaders of AI alike agree on one thing: intelligence explosion will change the world beyond recognition.

While Bill Gates, Stephen Hawking and countless others are broadly on the same page with Musk and Harris, some of the leading thinkers recognize that AI, like any other technology, is value-neutral. Gunpowder, after all, was first used in fireworks.

Ray Kurzweil argues that “AI will be the pivotal technology in achieving [human] progress. We have a moral imperative to realize this promise while controlling the peril.” And, in his view, humanity has ample time to develop ethical guidelines and regulatory standards.

Making computers part of us, part of our bodies, is going to change our capabilities so much that one day, we will see our current selves as goldfish.

As the world edges towards singularity, future technology is bound to enhance the human experience in some way, and it is up to us to make sure it is for the better.

The critics and cheerleaders of AI alike agree on one thing: intelligence explosion will change the world beyond recognition. When thinking about the future, I found the metaphor offered by Vernor Vinge, on the Invisibilia podcast, especially stark: “making computers part of us, part of our bodies, is going to change our capabilities so much that one day, we will see our current selves as goldfish.” If this is a true extent of our expected AI-and-Tech-powered evolution, our contemporary norms and conventions go straight out of the window.

Putting the war and AI in the same sentence, we anthropomorphize the latter.

Even if the accurate predictions are a dud, shouldn’t we at least attempt to apply the prism of exponential technologies to review our basic assumptions, question fundamentals of human behavior, and scrutinize our societal organization? AI’s promise could be an apocalypse or eternal bliss or anything in between, but, as we speculate on the outcome, we are making a value judgment. And here we ought to recognize our susceptibility to the projection bias. It compels us to apply the present-day intellectual framing to ponder the future.

Putting the war and AI in the same sentence, we anthropomorphize the latter. When we worry about the robots and machine-intelligence causing mass unemployment, we must recognize that such anxiety is only justified if human labor remains an economic necessity. When we say that the spiraling-out-of-control tech progress will create more inequality, we assume that the idea of private property, wealth, and money will survive the fourth-industrial revolution.

It’s an arduous task to define the fundamental terms, much less to question them. But, perhaps, playing out a couple of scenarios could prove a useful exercise is circumventing projection bias.

Competition & Collaboration

The natural selection is, at its core, a multidimensional competition of traits and behaviors. It manifests itself in a basic competitive instinct that humans are all too familiar with. Evolutionary psychology postulates that the driver of human behavior is a need to perpetuate one’s genes. So Homo Sapiens evolved competing for mates, fighting for resources to feed the offspring, all with a singular objective to maximize their genes’ chances to be passed on.

When the algorithms are better at decision-making than humans, and we surrender much of our autonomy to them, how will our competitive instinct fare?

On the other hand, we are, according to Edward O. Wilson, “one of only two dozen or so animal lines ever to evolve eusociality, the next major level of biological organization above the organismic. There, group members across two or more generations stay together, cooperate, care for the young, and divide labor…” In other words, we might have to attribute the stunning success of our species to the fine balance we’ve maintained between competition and cooperation instincts.

What will be the point of resource competition in the world of abundance?

Whether general machine intelligence is imminent or even achievable, the idea of post-scarcity economy is gaining ground. If and when the automation of pretty much everything delivers the world where human labor is redundant, what will be the wider ramifications for our value system and societal organization? When the algorithms are better at decision-makingthan humans, and we surrender much of our autonomy to them, how will our competitive instinct fare?

What will be the point of resource competition in the world of abundance? Is it possible that our instinct to compete slowly evaporates as a useful construct? Could we evolve to live without it? Unlike ants and bees that cooperate on the basis of rigid protocols, humans are spectacularly adaptable in our cooperation abilities. According to Yuval Harari, that’s what ultimately underpinned the rise of sapiens to dominate the Earth. Is it conceivable that the need to compete turns into an atavism as the technic transformations described by Kurzweil begin to materialize?

Economy

How can we be sure that the basic pillars of our economic thinking (e.g. private property, ownership, capital, wealth, etc.) will survive post-scarcity? 100 years from now, will anybody care for labor productivity? How relevant could our policies encouraging employment be when all of the humanity is freeriding on the “efforts” of the machines? What are we left with, when the basics such as supply and demand have been shuddered?

If ownership is pointless and money is no longer a useful unit of exchange, how will we define status?

To a gainfully employed person, today, a prospect of indefinite leisure might appear more of a curse than a blessing. This sentiment, viewed through the lens of natural selection, makes sense. The economic contribution by all able members of society would’ve been preferred to the mass pursuit of idleness. But should we be projecting the same trend into the future? What may sound like decadence and decay to us now, may be construed quite differently in the world no longer powered by the known economic forces.

The working assumption is that no matter what, someone will have to own the machines and pay for goods and services. Yet the idea of property and money is nothing more than social constructs that we all agreed on. If ownership is pointless and money is no longer a useful unit of exchange, how will we define status?

Certainly, the questions are plentiful and the answers are few. And I, for one, am in no position to offer concrete proposals or defend, admittedly, speculative arguments. The bottom line is that we are firmly on the path tosubvert the forces of evolution, which were, since the dawn of time, main drivers of our behavior. As political and religious dogmas have changed, the very basic economic principle remained — satisfying human needs and wants required human efforts. Those fundamental forces are clearly threatened by the accelerating pace of tech progress, singularity notwithstanding.

The ideas presented here may sound utopian and naïve. And Elon Musk may as well be right: the invention of AI could spell the end of human race. It is humanity’s awesome responsibility, therefore, to design proper governance for artificial intelligence and think it through before we take a plunge. When contemplating the future, we must be cognizant of the limits of our understanding and thus make use of our imagination — a distinctly human trait, at least for the time being.