Source: en.brinkwire.com

Driverless truck startup Starsky Robotics is shutting down, but not before sharing some cold hard truths about the autonomous driving industry. Founded in 2015, Starsky proposed a combination of self-driving and remote control for a fleet of next-generation trucks, saving full autonomy for the highway.

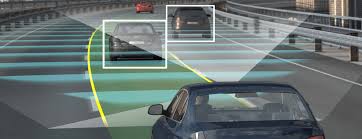

Rather than build a driverless truck that could handle every situation, Starsky’s plan was to mix autonomous systems with human teleoperation. On the highway, a relatively controlled environment, the truck would drive itself. That way, the demands for skilled operators would be significantly reduced.

In trickier situations, however – effectively “the first and last mile,” as Starsky explained it – a human driver would take over the controls. They wouldn’t be physically present in the truck, mind. Instead they’d use remote controls to pilot the rig from a distance.

Back in 2019, Starsky demonstrated the first fully-unmanned truck to drive on a live, public highway. Now, though, the company is shutting down. In a blunt post-mortem of what went wrong, founder and CEO Stefan Seltz-Axmacher blamed results-hungry investors, unexpected difficulties with getting the AI right, and the fact that safety just isn’t sexy for Starsky’s problems – and the problems that he predicts will impact the self-driving industry as a whole.

“There are too many problems with the AV industry to detail here,” Seltz-Axmacher writes, “the professorial pace at which most teams work, the lack of tangible deployment milestones, the open secret that there isn’t a robotaxi business model, etc. The biggest, however, is that supervised machine learning doesn’t live up to the hype. It isn’t actual artificial intelligence akin to C-3PO, it’s a sophisticated pattern-matching tool.”

The issue, he explains, is that matching – and eventually exceeding – human drivers’ abilities with edge cases is much tougher than most realized. Everyday driving in reasonable conditions is fairly low-hanging fruit; that can be achieved relatively rapidly. Developing a system that is capable of reacting safely to unexpected situations, however, is far trickier, and as you refine the self-driving AI you also set yourself the challenge of finding increasingly specific risk models with which to test.

Adding to that problem is the fact that, while safety is often cited as a primary concern for people when asked about whether they’d get into an autonomous vehicle, it’s actually a tough thing to get people excited about. The same, Seltz-Axmacher says, goes for investors. Starsky spent almost two years working on safety engineering, but “the problem is that all of that work is invisible,” he writes.

“Investors expect founders to lie to them,” the Starsky founder explains, “so how are they to believe that the unmanned run we did actually only had a 1 in a million chance of fatality accident? If they don’t know how hard it is to do unmanned, how do they know someone else can’t do it next week?”

At the end of 2019, the company’s attempts to raise more money fell flat. It’s currently seeking to sell off its patents as the company breaks apart. Seltz-Axmacher says he sees real autonomy still being 10 years out; “no one should be betting a business on safe AI decision makers,” he concludes.