Source: qz.com

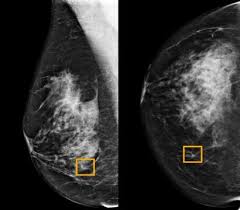

Google is working on an AI tool for mammograms that researchers hope will one day be more accurate than human radiologists. The tech giant paid for a study, the results of which were published last week (Jan.1) in Nature.

Its findings, at first glance, look promising. But experts caution that AI has a long way to go before it can replace a trained human—especially when it comes to accurately spotting breast cancer in diverse racial and ethnic populations.

Google first trained its AI on mammograms from 76,000 women in the UK and 15,000 women in the US, all who had received a positive diagnosis of breast cancer. It then tested its tool against mammograms of 28,000 other women, only some of whom had breast cancer, and compared its assessment to that of human radiologists. On scans from the US, Google’s AI cut false negatives by 9.4% and false positives by 5.7%; on scans from Britain, the AI cut down those errors by 2.7% and 1.7%, respectively.

But the Google study doesn’t account for the racial makeup of the women studied, which has given researchers pause. A Google spokesperson told Quartz that while information on race was originally collected by healthcare providers, its research team didn’t have access to such identifying details in the data made available to them.

“We already know that there are widespread racial inequalities in the healthcare system that have life or death consequences for patients,” says Sarah Myers West, a postdoctoral researcher at the AI Now Institute at New York University. Before AI tools like the one created by Google are deployed more widely, West says, it’s critical that they don’t reflect or even amplify those inequalities.

In England, for example, black women are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with advanced breast cancer as their white counterparts, according to a 2016 analysis from Cancer Research UK and Public Health England. Although black women are less likely to suffer from breast cancer as a whole, they have lower survival rates, according to data from the NHS Cancer Intelligence Network.

Researchers are still exploring why black women with breast cancer are more likely to get aggressive tumors than white women; black women in the UK are less likely to get breast cancer screenings, and public health campaigns neglect to target them specifically. Breast cancer rates for South Asian women in the UK have also risen in recent years, putting the group at an 8% higher rate of breast than white women, according to a University of Sheffield study.

In the US, the racial disparity is similar. White women in the US have a slightly greater risk of contracting breast cancer than their black counterparts, but lower mortality rates, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation. This trend isn’t reflected in Hispanic, Asian, and Native women, who experience the lowest diagnosis and mortality rates.

For AI to accurately predict breast cancer for all women, it’s crucial that the data used to train the system is reflective of the wider population. But these underlying disparities in the treatment of breast cancer mean that preexisting data sets don’t represent all populations.

“Artificial intelligence systems work by identifying patterns in large pools of data—in this case, looking for patterns in mammogram images and linking them to diagnoses—in order to make predictions about future data,” said West. Both the US and the UK, despite their diverse populations, are still countries where the majority identify as white. Training an AI model on a data set from these nations, without weighing race, stands to perpetuate existing racial biases.

There’s been some work on remedying racial bias in AI. Last year, MIT created a AI model that it claimed could predict breast cancer effectively in black and white women. But MIT’s model still relied on a relatively small number of non-white participants. Of the women whose mammograms were used to train the model, 81% were white, 5% were black, 4% were Asian, and 8% were either marked as “other” or “unknown.”

Even if these issues were addressed, AI diagnosis wouldn’t be right for everyone. The value of mammograms—whether they’re evaluated by a human or a machine—is fiercely debated. Recent studies suggest that routine screenings can lead to overdiagnosis of breast cancer, identifying growths that don’t necessarily develop into life-threatening cancers. In those cases, treatments including radiation and surgery may prove more risky than the growths themselves.

Fortunately, Google’s model isn’t ready for prime time yet. Google plans to work with additional partners around the world to build its data set before making it available to hospitals. “We will continue to explore and build upon our model, working with additional partners across the world, before considering bringing it into clinical practice,” said Shravya Shetty, a Google researcher who co-authored the paper, in an email to Quartz. Google didn’t clarify how future models would address racial diversity.