Source – techrepublic.com

Ask what Amazon’s greatest accomplishment has been to date, and you’ll probably hear about how they’ve revolutionized online shopping, or become a credible player in media and entertainment. If you speak with a technologist, they might mention Amazon’s emergence as one of the preeminent technology platforms. While there’s nothing new or exciting about companies using Amazon Web Services (AWS) as a platform, consider for a moment what would happen if you travelled back in time and told your previous self that you’d soon come to rely on Amazon as a critical infrastructure partner.

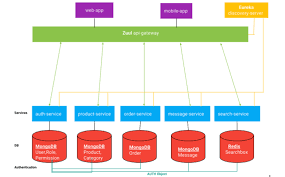

Public information seems to indicate that Amazon didn’t really set out to become a major cloud player, and early versions of its platform were ultimately built for internal consumption. In the early 2000s, Amazon set a conceptually simple, but far-ranging policy that all company IT projects needed to provide a standardized interface that separated the service from the underlying technology since it’s IT stack had grown into what the company described as a huge “monolith” that was becoming nearly impossible to maintain.

Rather than building custom interfaces to an order tracking system that would need to be changed should the underlying order tracking software be updated or changed, the group that maintained the order tracking system would publish a set of standard APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) that would document how other applications could ask for and receive order tracking data. These interfaces were essentially standards, and could not be modified without appropriate communication to users, as well as a defined timeline for any changes to existing interfaces.

Furthermore, these standardized interfaces would be designed to accomplish a single, discrete task, hence the “micro” in microservice. In traditional systems design, you might pass data to another application that then performs dozens of operations on that data, effectively hiding what occurred from someone else who might wish to use the service.

The magic of microservices

What Amazon quickly realized was that with all of its systems providing simple, common, and stable microservices, other parts of the company, and ultimately the public at large, could use these services to create something new, and the products built with Amazon’s internal technology were freed from the vagaries of version upgrades, system changes, and code updates, since they could always depend on a service producing a consistent result, irrespective of the technology used to provide that result.

How to get started with microservices

For a few organizations, it may be possible to duplicate Amazon’s move and essentially mandate all new software projects be delivered through microservices. For the rest of us, it may be easier to start more simply. Probably the best place to start simply is when acquiring new software or platforms. This is generally simple when buying cloud software as a service, as providers deliver a suite of pre-built microservices to interact with the data and business logic.

Identify some simple use cases that show the benefit of microservices. For example, if you implement a cloud-based sales platform, you might leverage microservices to capture data on your website and feed it into the sales system. Or, you might quickly develop a mobile or web-based app in record time that performs a specific, meaningful task and demonstrates that microservices make IT faster and more flexible. When hunting for areas to build such a test case, look for tech-savvy business users who are buried under spreadsheets, macros, and Access databases trying to essentially marry information from various services in your company. While this might seem like it’s creating more work for IT, ultimately IT should maintain and secure the microservice, while users create applications of that service.

How to avoid potential pitfalls

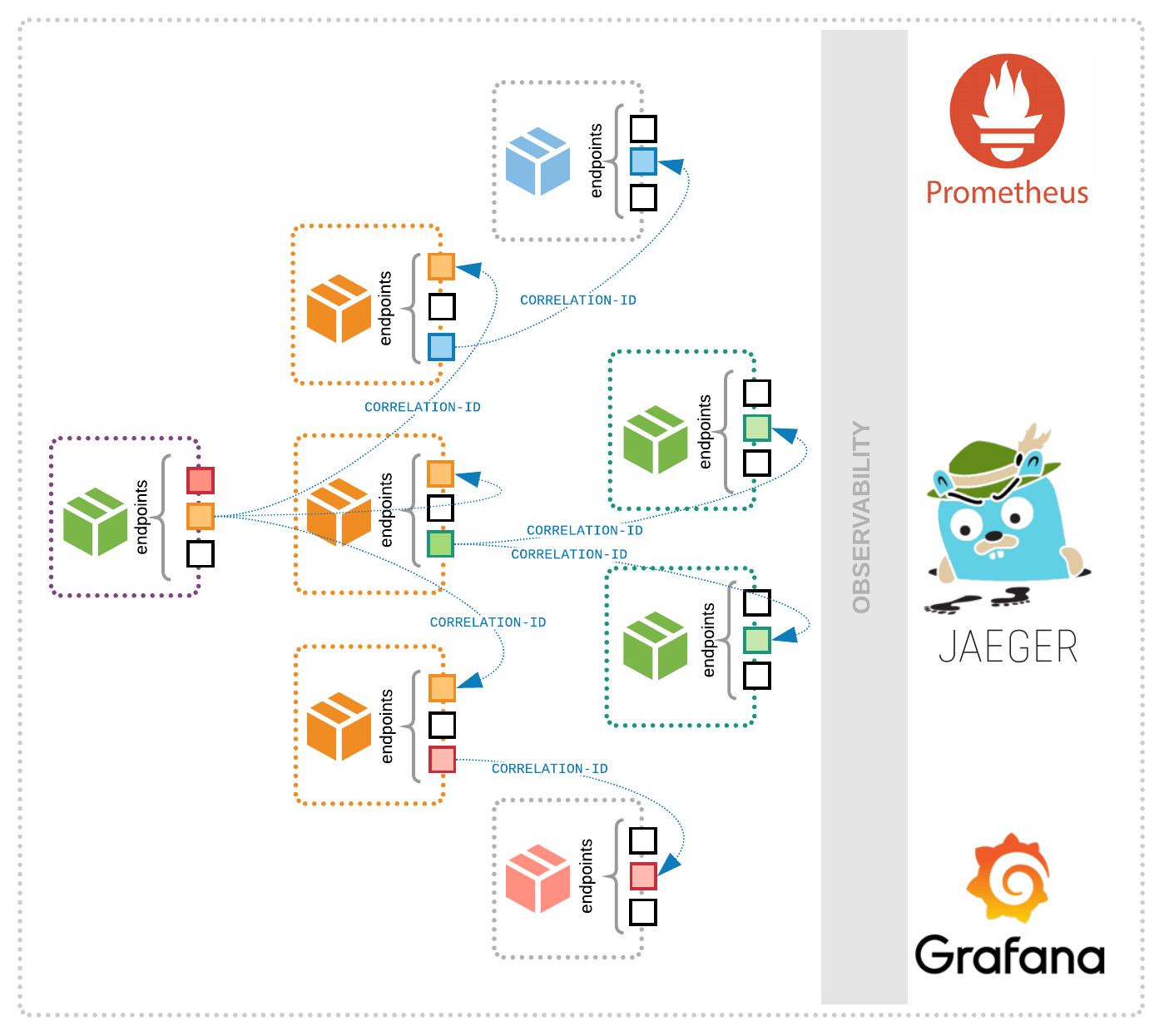

At a superficial level, it’s easy to convey the benefits of microservices. However, as you start to plan a transition to microservices the proposition can become daunting. Even small organizations have hundreds or thousands of application components that could be made available via a microservice.

Identify key IT services that power multiple applications and prioritize them for microservices.

A shipping company might start by building order status microservices, just as a retailer might start with inventory services. It may also be tempting to create the perfect microservice for each application, that accommodates every potential scenario and permutation. This approach is a recipe for delayed rollouts and overcomplication. Seek to keep the “micro” in microservices by making each perform a discrete task. You can always augment multiple services to perform more complex functions, just as you can expand functionality in future versions.

For each service, publish a set of specifications that is maintained on an ongoing basis.

A comprehensive library of microservices that are not shared or well-documented accomplishes little. Remember that a key benefit of microservices is that new applications can be built without complex IT projects and approvals, so keeping your services updated and documented is critical for getting the benefit of these services.

Allow for ownership of microservices.

There may also be some resistance by owners of the various services that will ultimately be made available via a microservice architecture. With open services, individual teams give up some of their “gatekeeper” role, which can seem threatening. Ensure that you communicate that their span of control remains intact by preserving the integrity of what happens behind the microservice, and that the broader organization can rapidly benefit from their work rather than having to wait for complex, one-off interfaces.